The music industry is undergoing a major paradigm shift. After the homogenisation of the major labels, we now see a massive rise of independent record companies.[1] In a way, this is not surprising. The three remaining majors, Sony, Warners, and Universal are industrialised enterprises; they invest in music and are interested in talent, but all of this with the main goal of commercial profit. They “held all the cards and could manipulate and orchestrate the marketplace to do whatever they wanted,”[2] held being the key word, as we see a growth of small independent labels. The monopolising labels are an example of what has been described as the commercialisation and routinisation of culture and cultural products, or the military industrial complex.[3] The monopolising labels produce albums through pre-formulated strategies, from production to marketing and from social media to tours. This way, companies can produce and release more albums at a quicker pace, resulting in a higher profit.

|

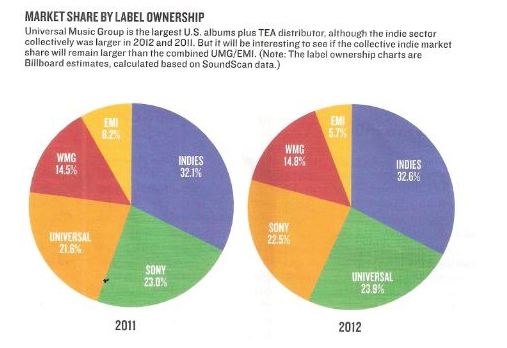

| The market share of independent labels is growing |

Independents however, seem to act out of love of music and a passion for the craft. And exactly this affection is what differentiates the little labels in today’s market. We, the consumers of music, do no longer make our musical decisions solemnly based on what those with the money, the majors, tell us. Through social media and the use of the Internet we have agency, and we use that agency to listen to the music we like, whether the artist is signed with Sony or an indie. Something that we found very interesting is, that within the record label industry, there are musicians ditching their old label to start one themselves. This blog will look at some of these musicians and how the workings of the creative industries and the consumption of culture in today’s global society allows for these musicians to become independent label owners. We are certainly not trying to downplay the complex workings of the music industry but rather shining a light on the increasing number of independent labels owned by musicians and why this increase is possible in today’s society.

The phenomenon of musicians-turned-label-boss is not new, bands like The Rolling Stones and The Beatles also started their own labels back in the day. But they released their own music, rather than exposing (new) artists, which is what is more common today. It is likely that marketing of an artist in the sixties and seventies was still very dependent on the kind of money and means available only through the majors. Today, though the majors are still influential, music does not depend solemnly on those labels anymore. Through the power of social structures and consumer agency these independent labels have a market, since individuals are “more aesthetically reflexive and semiotically literate.”[4] Consumers are capable of ignoring the majors, instead investing in music they connect with, whether or not that music comes with the spectacle we often see with major releases by the Big Three. A successful musician can now launch a new career by posting a video on social media, or, in other words, through the convergence “of different media and technologies [musicians can] tell their stories using different platforms, engaging consumers [fans] on different levels, using different media at the same time.”[5] Moreover because all other tasks can be outsourced, a musician can start a label with the romantic notion of exposing new talent.[6] As Ed Sheeran recently said when talking about his label Gingerbread Man Records, “I don’t do much of the work, most of the work is done by my team.” He does not busy himself with “crunching numbers or worrying about deadlines and meetings.” Sheeran seems to adapt more of a guiding position, rather than offering the business know-how and contacts, as the more traditional labels tend to do.

In 2001, musician Jack White started his now highly successful label Third Man Records. Today the label is situated in Nashville, Tennessee and has expanded to include a music venue, recording studio, video studio, distribution center, vinyl press plant, and a novelties & record store. First, it is interesting to realise that the blurring of the line between professional and amateur creatives, which is what happens when musicians launch their own label, is actually a form of media convergence. There is a certain agency at play that allows these musicians to “embody, perform, reflect on, and actually become media producers,”[7] or in this case a record label owner. It seems like the consumer values the opinion of what artists like Jack White and Ed Sheeran find interesting. Moreover, as Third Man employee Ben Blackwell points out, “anything we can do in-house we want to do in-house. Whether this is visual design, whether it is pick-and-pack mail order, shipping, web design, running the fan club, all that stuff. Putting on live-shows, having our own record store.” By keeping everything within the company, Third Man is controlling both the management of creativity and the commercial side.”[8] Third Man Records is a prime example when looking at the blurring of “boundaries between economy and culture,” and moreover the importance of symbolic value within a commercial business.[9] Making money may not be the main motive, it is still a condition for the label’s existence.

As the video above shows, Third Man Records has created an experience beyond the literal consumption of music, something that can be considered almost alien in today’s society, where most of the music is consumed digitally and online. But there is market for the physical experience of engaging music outside of actual live performances. Important to note here, is that Third Man is situated in Nashville, and close to New Orleans and Memphis. Together these cities form a triangle of creative cities with a rich musical culture. These cities are not only buzzing with professionals and (wannabe) musicians, but also tourists that come to experience this musical culture. It makes sense for Third Man to have a market within the triangle, as the clustering of creative talent and resources tends to “catalyse a flurry of economic, cultural, and social activities in those regions, reinvigorating those areas.”[10]

Moreover, what Third Man does very brilliantly is hooking onto the growing popularity of vinyl, not only by releasing their new music through this format, but also re-releasing valuable recordings, for example by partnering up with the legendary Sun Studios to re-release classic singles. We can see here that the “behaviours and passions of consumers have become more likely to propel business into action, steering product development innovation and differentiation.”[11]

|

| The winner of Joss Stone's cover art contest. |

Another artist that set up her own label to pursue making music rather than money is Joss Stone. On multiple occasions Stone advocated in favor of people consuming music of established artists for free and give money to starting artists. By saying that people can download music for free anyway, Joss Stone highlights how “social structures do not always conform with the processes inferred by industrialisation.”[12] Joss Stone makes use of the modern phenomenon that “users and consumers [are also] producers and prosumers,”[13] and organised a contest where individuals could submit their version of the next album’s artwork. Her own label, under which the album was released, allowed Stone the creative control over things such as the cover art.

The rise of independent labels, and in this case labels owned by established musicians, is both interesting and fascinating to look at in relation to the changes that are occurring in the media industries. The Internet is seen as possibility homogenising, since local cultures become more and more globalised. But as we see with the rise of independents, there is also a growing market for smaller labels that are not focused as much on creating the biggest revenue and producing music for the masses, but rather care more about the creative freedom often not permitted by the major labels. Ed Sheeran signed his first artist, Jamie Lawson, because he believes in his talent. Sheeran’s (online) popularity can be used to promote Lawson through social media. Here we see one example of how globalisation and digitalisation allow for independent records to carry success, as they can easily and cheaply build on existing online networks. Moreover Joss Stone started her label to get back her creative freedom, by doing the things she personally believes in. Stone used her network to encourage audience participation by setting up an album-cover design contest. Lastly this blog looked at Jack White’s Third Man Records, a business that goes beyond the releasing of (new) music, showing how media convergence allows for success in the label industry, even as a non-professional. The Third Man case study also proves how (small) creative businesses are important to thriving cities, and that by

|

| Recording your own song directly on disc is part of the experience of Third Man Novelties & Record Store |

making use of the rising popularity of vinyl and the growing interest in the shopping experience (or experience economy), that there is still a physical market for a business that has been predominantly digital over the past decade. The bottom line is, that the labels discussed in this blog can exist because audiences and consumers are letting them exist, by putting time, effort, and money into it.

We highlighted the rise of the independents but which way do you think the industry will go?

DL, NS, EH, LD, KH

[1]“Independent music is a growing force in the global market,” musicbusinessworldwide.com, July 21, 2015, accessed October 7, 2015, http://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/independent-music-is-a-growing-force-in-the-global-market/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Schiller & Phillips qtd in Vicki Mayer “Making Media Production Visible.”

[4] Mark Deuze, “Creative Industries, Convergence Culture and Media Work,“ in Media Work, 47

[5] Ibid, 71.

[6] Vicki Mayer “Making Media Production Visible,” in The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2013), 10.

[7] Vicki Mayer “Making Media Production Visible,” 4.

[8] Mark Deuze, “Creative Industries, Convergence Culture and Media Work,“ 65.

[9] Ibid, 46.

[10] Mark Deuze, “Creative Industries, Convergence Culture and Media Work,“ 50

[11] Ibid, 47.

[12] Vicki Mayer “Making Media Production Visible,” 3.

[13] Ibid, 21.

Bibliography

Deuze, Mark. “Creative Industries, Convergence Culture and Media Work.“ In Media Work.

Bibliography

Deuze, Mark. “Creative Industries, Convergence Culture and Media Work.“ In Media Work.

Mayer, Vicki. ”Making Media Production Visible.” In The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2013.

“Independent music is a growing force in the global market.” Musicbusinessworldwide.com. July 21, 2015. Accessed October 7, 2015, http://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/independent-music-is-a-growing-force-in-the-global-market/.